14 Mar 2012 ... From "One Bullet Away" by Nathaniel Fick ...

President Harry Truman once said that the Marines had a propaganda machine

second only to Stalin's. He was right. My impression of the Corps, even as a

newly commissioned officer, was one of a lean, mean, fighting force, all teeth

and no tail. I was shocked when my platoon commander, Captain McHugh, told his

assembled lieutenants that only ten percent of us would be infantry officers.

The rest would go to the other combat arms - artillery, amphibious assault

vehicles, and tanks - or to support jobs such as supply, administration, and

even financial management.

McHugh asked us to keep an open mind and learn about each job before deciding

which to compete for. I nodded but knew that only one thing would satisfy me:

infantry officer. I wanted the purity of a man with a weapon traveling great

distances on foot, navigating, stalking, calculating, using personal skill. I

couldn't let a jet or a tank get in the way, and I certainly wasn't going to

sit behind a desk. I wanted to be tested, to see if I had what it takes. The

Marine Corps had recently unveiled a recruiting campaign using the motto

"Nobody likes to fight, but somebody has to know how." It was dropped because

Marines do like to fight and aspiring Marine officers want to fight.

The grunt life is untainted. I sensed a continuity with other infantrymen

stretching back to Thermopylae. Weapons and tactics may have changed, but they

were only accoutrements. The men stay the same. In a time of satellites and

missile strikes, the part of me that felt I'd been born too late was drawn to

the infantry, where courage still counts. Being a Marine was not about the

money for graduate school or learning a skill; it was a rite of passage in a

society becoming so soft and homogenized that the very concept was often

sneered at.

8 Mar 2012 ...

Jake Campbell has gone "to explore strange new worlds, to seek out new life and

new civilizations, to boldly go where no [sane] man has gone before." For the

next 6 months he will be enjoying the "secret family recipe" known as The Basic School

(aka TBS). Putting the "The" in the title is not a function of hubris,

it's so that the acronym wouldn't be "BS". TBS is a tenant of Marine Corps

Base Quantico - located 34 miles SW of Washington D.C.

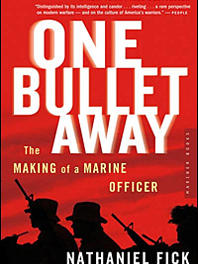

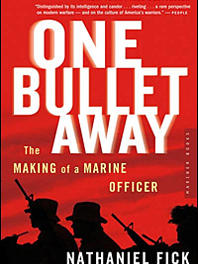

The book "One Bullet Away - the Making of a Marine Officer" has an excellent

chapter on the author's experience at TBS. I would like to offer a weekly

excerpt from the book so we can vicariously experience the Campbell

pilgrimage.

From "One Bullet Away" by Nathaniel Fick ...

The TBS campus, called Camp Barrett, looks more like a dilapidated community

college than the cradle of the Marine officer corps. On my first Monday

morning, I watched lieutenants hurrying back and forth between classes. They

carried brief bags and plastic coffee mugs, like graduate students. Camp

Barrett's dozen anonymous buildings include two barracks, several classrooms, a

pool, a theater, and an armory, all surrounded by flat expanses of grass that

double as playing fields when not being used as helicopter landing zones.

The compound's only distinctive feature is Iron Mike, a bronze statue of a

Marine holding a rifle in his right hand and waving on unseen men with his

left. It was next to Iron Mike that our class assembled that morning. I stood

by the statue, conscious that I was being intentionally steeped in the history

of the Corps and its heroes. Around me stretched the six platoons of Alpha

Company, 224 newly commissioned second lieutenants. [There are usually six

companies in TBS at one time; with start and graduation dates every two

months.]

We would spend the next six months at Camp Barrett, learning all the basic

skills we would need as Marine officers. The Corps' mantra is "Every Marine a

rifleman." Its corollary is "Every Marine officer a rifle platoon commander."

In the Marine Corps, jet pilots, clerks, and truck drivers are all infantrymen

first. TBS would teach us those basic infantry skills, plus all the rules,

regulations, and administrative requirements that are part of a peacetime

military. The greatest topic of conversation at TBS was MOS selection.

Military Occupational Specialties are the specific jobs in the Corps - aviator,

artillery, logistics, tanks, infantry, and others - and they're competitive.

We would be assigned to the various specialties according to class rank. The

most coveted of them was infantry.

|

Nathaniel Fick does an excellent job

chronicling his pilgrimage from Officer Candidate School (OCS, 1998), to The

Basic School (TBS), to Infantry Officer School, to the fleet, to Afghanistan

(2001), to Marine Recon, to Iraq (2003), to civilian life.

| |

|

TBS Web page

Class Report Date Start Date Graduation

Echo 5-11 Jun 07, 2011 Jun 20, 2011 Dec 14, 2011

Fox 6-11 Jul 05, 2011 Jul 18, 2011 Jan 26, 2012

Golf 7-11 Aug 16, 2011 Sep 06, 2011 Mar 07, 2012

Alpha 1-12 Oct 18, 2011 Oct 31, 2011 May 09, 2012

Bravo 2-12 Dec 16, 2011 Jan 09, 2012 Jul 03, 2012

Charlie 3-12 Mar 06, 2012 Mar 19, 2012 Sep 12, 2012

Delta 4-12 Jun 05, 2012 Jun 18, 2012 Dec 12, 2012

Echo 5-12 Jul 05, 2012 Jul 16, 2012 Jan 23, 2013

Fox 6-12 Sep 04, 2012 Sep 17, 2012 Mar 27, 2013

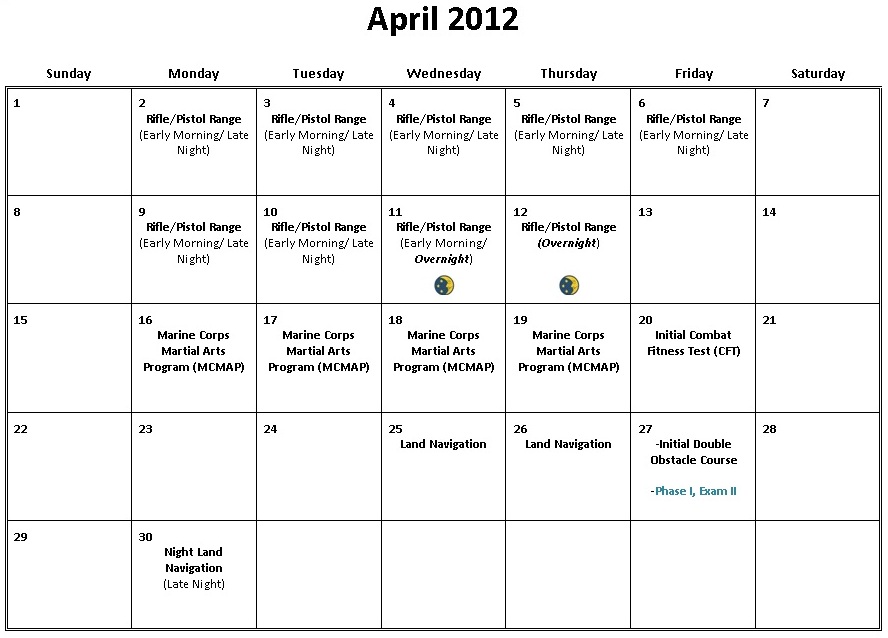

Following the successful completion of Rifle Week, the lieutenants of Charlie

Company began their training in the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP).

Drawing inspiration from a number of different martial arts styles, MCMAP seeks

to equip Marines not only to prevail in hand-to-hand and close quarters combat,

but also to be better and more confident leaders. Instruction in MCMAP is

predicated upon growth in three core disciplines: Mental, Physical, and

Character. The development of the mental aspect of MCMAP stresses situational

awareness, decision making, and threat assessment. It also includes "Warrior

Studies," in which Marines discuss the achievements of warriors who showed

exemplary service on the battlefield. The physical aspect of MCMAP includes the

development of strength and muscular endurance, as well as familiarizing

Marines with MCMAP techniques. Character development involves the discussion of

ethics, morality, and the Marine Corps core values of honor, courage, and

commitment.

Following the successful completion of Rifle Week, the lieutenants of Charlie

Company began their training in the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP).

Drawing inspiration from a number of different martial arts styles, MCMAP seeks

to equip Marines not only to prevail in hand-to-hand and close quarters combat,

but also to be better and more confident leaders. Instruction in MCMAP is

predicated upon growth in three core disciplines: Mental, Physical, and

Character. The development of the mental aspect of MCMAP stresses situational

awareness, decision making, and threat assessment. It also includes "Warrior

Studies," in which Marines discuss the achievements of warriors who showed

exemplary service on the battlefield. The physical aspect of MCMAP includes the

development of strength and muscular endurance, as well as familiarizing

Marines with MCMAP techniques. Character development involves the discussion of

ethics, morality, and the Marine Corps core values of honor, courage, and

commitment. Proficiency in MCMAP is measured by belt levels, much like other martial arts

such as karate or taekwondo. The belt progression begins with tan belt, moving

up through gray, green, brown, and six degrees of black belt. During MCMAP

week, Charlie Company received entry level tan belt training. The tan belt

curriculum includes basic strikes (punches, kicks, and elbow and knee strikes),

bayonet and knife techniques, chokes, joint manipulations, and throws. In

total, over 50 different techniques were learned and mastered.

Proficiency in MCMAP is measured by belt levels, much like other martial arts

such as karate or taekwondo. The belt progression begins with tan belt, moving

up through gray, green, brown, and six degrees of black belt. During MCMAP

week, Charlie Company received entry level tan belt training. The tan belt

curriculum includes basic strikes (punches, kicks, and elbow and knee strikes),

bayonet and knife techniques, chokes, joint manipulations, and throws. In

total, over 50 different techniques were learned and mastered. The purpose of combat conditioning is defined in the name itself. It is meant

to prepare your body for the physical rigors experienced in combat. The average

combat load per Marine is about 80 lbs. A combat load includes radios, weapons,

ammo, chow, water and any necessary gear needed for that mission. In any

mission, a Marine is expected to move quickly and efficiently with the extra

weight. That can include but is not limited to running, jumping, climbing, and

crawling. The list also includes being able to evacuate a fellow Marine with a

full combat load.

The purpose of combat conditioning is defined in the name itself. It is meant

to prepare your body for the physical rigors experienced in combat. The average

combat load per Marine is about 80 lbs. A combat load includes radios, weapons,

ammo, chow, water and any necessary gear needed for that mission. In any

mission, a Marine is expected to move quickly and efficiently with the extra

weight. That can include but is not limited to running, jumping, climbing, and

crawling. The list also includes being able to evacuate a fellow Marine with a

full combat load. 23 May 2012 ... An article by 2ndLt Davis in the Charlie Company monthly

newsletter ...

23 May 2012 ... An article by 2ndLt Davis in the Charlie Company monthly

newsletter ... ... I left the Corps because I had become a reluctant warrior. Many

Marines reminded me of gladiators. They had that mysterious quality

that allows some men to strap on greaves and a breastplate and wade

into the gore. I respected, admired, and emulated them, but I

could never be like them. I could kill when killing was called for,

and I got hooked on the rush of combat as much as any man did. But

I couldn't make the conscious choice to put myself in that position

again and again throughout my professional life.

Great Marine commanders, like all great warriors, are able to kill that

which they love most - their men. It's a fundamental law of warfare.

Twice I had cheated it. I couldn't tempt fate again.

... I left the Corps because I had become a reluctant warrior. Many

Marines reminded me of gladiators. They had that mysterious quality

that allows some men to strap on greaves and a breastplate and wade

into the gore. I respected, admired, and emulated them, but I

could never be like them. I could kill when killing was called for,

and I got hooked on the rush of combat as much as any man did. But

I couldn't make the conscious choice to put myself in that position

again and again throughout my professional life.

Great Marine commanders, like all great warriors, are able to kill that

which they love most - their men. It's a fundamental law of warfare.

Twice I had cheated it. I couldn't tempt fate again. She paused, as if waiting for me to disavow the quote. I was

silent, and she went on. "We have a retired Army officer on our staff, and he

warned me that there are people who enjoy killing, and they aren't nice to be

around. Could you please explain your quote for me?"

She paused, as if waiting for me to disavow the quote. I was

silent, and she went on. "We have a retired Army officer on our staff, and he

warned me that there are people who enjoy killing, and they aren't nice to be

around. Could you please explain your quote for me?"

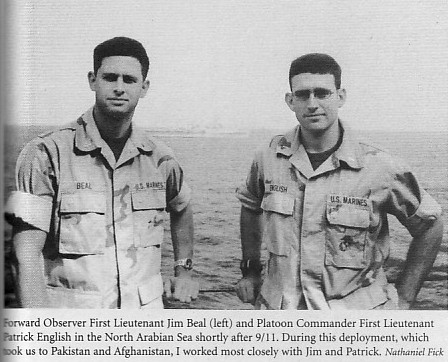

Marines crowded the flight deck. Only an hour after the attacks half

a world away, most the the Dubuque's sailors and Marines were already

back aboard and far more restrained than usual this late on a night

in port. My platoon milled around, clad in sandals and Hawaiian shirts.

No one spoke. On the stern, two sailors manned a machine gun. They

trained it on the cars depositing passengers at the gangplank. The

ship rumbled and smoked from its funnel. The Dubuque was making steam,

getting ready to sail.

Marines crowded the flight deck. Only an hour after the attacks half

a world away, most the the Dubuque's sailors and Marines were already

back aboard and far more restrained than usual this late on a night

in port. My platoon milled around, clad in sandals and Hawaiian shirts.

No one spoke. On the stern, two sailors manned a machine gun. They

trained it on the cars depositing passengers at the gangplank. The

ship rumbled and smoked from its funnel. The Dubuque was making steam,

getting ready to sail.